Food and farm prices have been a major concern for politicians and pundits alike for more than a century, and the food supply chain has become ever more complex.

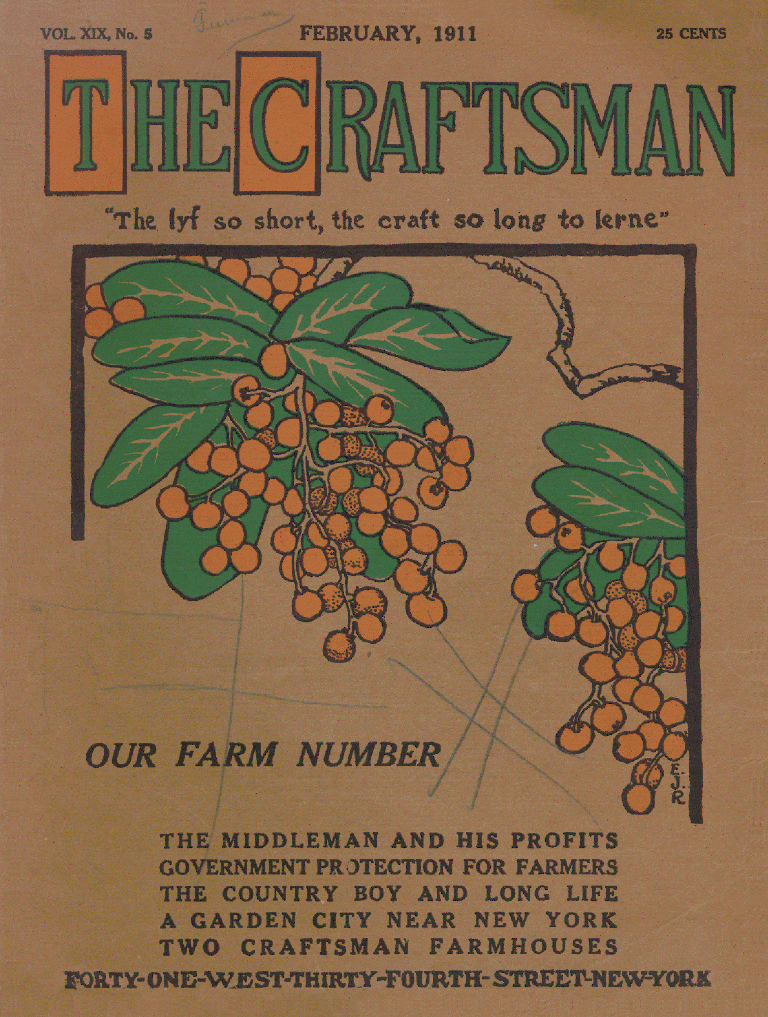

Following is an article taken from the February 1911 issue (Volume XIX, Number 5) of The Craftsman, a magazine published to promote the ideals of simplicity, honesty, and truth and the principles of the American Craftsman movement. It was a movement which encouraged originality, simplicity of form, local natural materials, and the visibility of handicraft and advocated economic and social reform. Today The Craftsman would be lambasting Big Food and Big Ag and supporting organic food, local food production, and the growth of natural food co-ops and farmers’ marketing co-ops.

Following is an article taken from the February 1911 issue (Volume XIX, Number 5) of The Craftsman, a magazine published to promote the ideals of simplicity, honesty, and truth and the principles of the American Craftsman movement. It was a movement which encouraged originality, simplicity of form, local natural materials, and the visibility of handicraft and advocated economic and social reform. Today The Craftsman would be lambasting Big Food and Big Ag and supporting organic food, local food production, and the growth of natural food co-ops and farmers’ marketing co-ops.

In this piece, authored by Gustav Stickley, furniture manufacturer, design leader, publisher, and the promoter of the American Craftsman style, the writer takes a close look at the “spread” between the price the farmer gets for his products and the price the consumer pays for those products in the market. Nothing has changed and, in fact, the amount of “indebtedness” each item incurs has exploded as more and more middlemen have been added to the process. Stickley’s solution: buying clubs and food co-ops.

How things change and how they remain the same!!

(Editor’s Note: This is written in the style of the very early 20th Century, be patient!)

Cooperation to Stop the Leak Between Farmer and Consumer

By Gustav Stickley, Editor

Nearly a year ago The Craftsman suggested that the pinch of high prices, if it served to awaken us to the ugliness of waste and to the value of cooperation, might prove to be a blessing in disguise. We told how more than sixty years ago a group of simple English weavers, confronted by this same problem of making an inelastic wage stretch to keep pace with the mounting cost of necessities, found a solution in cooperative buying and selling – a solution which found such favor that now, according to a recent estimate, one in every four persons in Great Britain and Ireland is reaping the benefits of the cooperative method applied to the manufacturing, buying and selling of the necessities of life. The same principle – that of cutting off what is added to a commodity’s price during its passage from the producer to the consumer by eliminating the middleman – has been applied with varying degrees of success in Germany, France, Russia, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Italy, Denmark, and Austria-Hungary. While recognizing that the various attempts to transplant the cooperative movement to this country have hitherto failed to achieve a very vigorous growth – owing, possibly to the fact that the spirit of waste and speculation is still too deeply rooted in our national character – we predicted in the article already referred to, that the time would come when we would recognize the doorway of cooperation as the logical way of escape from the increasing pressure of high prices. As we then pointed out, a cooperative store, organized and managed on the basis of one of our big department stores, but with the profits returning to the consumer in the form of dividends, would have in it as many elements of business success as are to be found in the present department store system, with the additional advantage of materially reducing the cost of living to all its membership.

Fresh emphasis is given to this contention by a perusal of the Secretary of Agriculture’s annual report. While we can scarcely describe ourselves as a poverty-stricken nation in the face of last year’s record-breaking crops – the lump value of Uncle Sam’s farm products having reached the astounding sum of nine billion dollars – the depressing fact remains that the purchasing power of a dollar is today less than half what it was ten years ago. But, as Secretary [James] Wilson* reminds us, this is not the farmer’s fault. Nevertheless, of the three inescapable items in the cost-of-living problem – food, clothing and shelter – two at least lead us back past the retailer, the jobber, the commission man, and the carload shipper to the farmer and the stockman. But a large fraction of the consumer’s dollar must go into the pockets of each of these middlemen before the remnant reaches the producer. Or, to begin at the other end of the line, the commodity incurs indebtedness at every step of its journey from the producer to the consumer, and the latter settles the account. Secretary Wilson quotes figures, gathered some years ago by the Industrial Commission but still pertinent, to show that customers pay from 25 to 400 per cent more than the farmers receive for a long list of farm products that are used every day. After deducting a small percentage for freight rates the bulk of this increase in prices must be charged against the middlemen. And even so the middlemen and retailers are no unduly prosperous.

There were times prior to eighteen hundred and ninety-seven when the prices of farm products received by farmers were even less than the cost of production. But in the upward price movement which began in eighteen hundred and ninety-seven, these prices have advanced in a greater degree than those received by nearly all other classes of producers. It is generally admitted, however, that they have not at any time reached a figure that affords more than a reasonable return upon the farmer’s labor and investment. Moreover, as Secretary Wilson remarks, the price received by the farmer is one thing; the price paid by the consumer is another. To quote further from his latest report:

“The distribution of farm products from the farm to consumers is elaborately organized, considerably involved and complicated burdened with costly features. These are exemplified in my report for nineteen hundred and nine by a statement of the results of a special investigation into the increased cost of fresh beef between the slaughterer and the consumer.

“It was established that in the North Atlantic States the consumer’s price of beef was thirty-one and four-tenths per cent higher than the wholesale price received by the great slaughtering houses; thirty-eight per cent higher in the South Atlantic States; and thirty-nine and four-tenths per cent higher in the Western States. The average for the United States was thirty-eight per cent.

“It was fond that the percentage of increase was usually lower in the large cities than in the smaller ones and higher in the case of beef that is cheap at wholesale than of high-priced beef. It was a safe inference that the poorer people paid nearly twice the gross profit that the more well-to-do people paid. . . .

“It is established by the investigation of this Department made last June that the milk consumers of seventy-eight cities paid for milk an increase of one hundred and eight-tenths per cent above the price received by the dairymen; in other words, the farmer’s price was fully doubled. The lowest increase among the geographic divisions was seventy-five and five-tenths per cent in the South Atlantic States and the highest was one hundred and eleven and nine-tenths per cent in the Western States.

“In the purchase of butter the consumer pays fifteen and eight-tenths per cent above the factory price in the case of creamery prints, fifteen and six-tenths per cent above the factory price in the case of renovated butter. The percentages of increase among the five divisions of States do not vary much from the averages for the United States.

“Some large percentages of increase of prices were found by the Industrial Commission – one hundred and thirty-five and three-tenths per cent for cabbage bought by the head; one hundred per cent for melons bought by the pound, for buttermilk sold by the quart, and for oranges sold by the crate; two hundred and four-tenths per cent for onions bought by the peck; four hundred and four-tenths per cent for oranges bought by the dozen; one hundred and eleven and one-tenth per cent for strawberries bought by the quart; and two hundred per cent for watermelons sold singly.

“There were many cases of increase of consumer’s price over farmer’s price amounting to seventy-five per cent and over, but under one hundred per cent, and among these were ninety and five-tenths per cent for apples bought by the barrel and eighty and six-tenths per cent for apples bought by the box; seventy-five per cent for chickens bought by the head; eighty-three and our-tenths per cent for onions bought by the pound; eight and five-tenths per cent for potatoes bought by the bushel; eight-eight and eight-tenths per cent for poultry in general bought by the pound; ninety-five and eight-tenths per cent for strawberries bought by the box; eighty-two and five-tenths per cent for sweet potatoes bought by the bushel.

“It may be worth while to extend the list of farm products that are sold to consumers at a large increase above farm prices. It the class of commodities selling for an increase of price amounting to fifty per cent and over but under seventy-five per cent above farm prices may be mentioned the following increases: sixty-one and eight-tenths per cent for cabbage bought by the pound; sixty-six and seven-tenths per cent for celery bought by the bunch, turnips and parsnips bought by the bunch, and green peas bought by the quart; fifty-four and four-tenths per cent for chickens bought by the pound; fifty per cent for eggplants bought by the crate; sixty-eight and four-tenths per cent for onions bought by the bushel; sixty-eight and seven-tenths per cent for oranges bought by the box; sixty per cent for potatoes bought by the peck; fifty-nine and eight-tenths per cent for turkeys bought by the pound.”

These figures, Secretary Wilson contends, make it clear that the problem is one for the consumer, not the farmer, to remedy. The former has no well-grounded complaint against the latter for the prices he pays. The farmer supplies the capital for production and takes the risk of losses from drought, flood, heat, frost, insects and blights. He supplies hard, exacting, unremitting labor. Moreover –

“A degree and range of information and intelligence are demanded by agriculture which are hardly equaled in any other occupation. Then there is the risk of overproduction and disastrously low prices. From beginning to end the farmer must steer dexterously to escape perils to his profits and indeed to his capital on every hand. At last the products are started on their way to the consumer. The railroad, generally speaking, adds a percentage of increase to the farmer’s prices that is not large. After delivery by the railroad the products are stored a short time, are measured into the various retail quantities, more or less small, and the dealers are rid of them as soon as possible. The dealers have risks that are practically small, except credit sales and such risks as grow out of their trying to do an amount of business which is small as compared with their number.

“After consideration of the elements of the matter, it is plain that the farmer is not getting an exorbitant price for his products, and that the cost of distribution from the time of delivery at destination by the railroad to delivery to the consumer is the feature of the problem of high prices which must present itself to the consumer for treatment.”

The farmers have already, in many parts of the country, formed cooperative associations for the selling of their products. Secretary Wilson suggests that consumers, taking a leaf from the farmer’s books, might at once break up the vicious conditions that result in high retail prices for foodstuffs by forming voluntary associations of their own, which should buy directly from the associations of farmers. He admits, of course, that there are still obstacles to overcome before this remedy can prove entirely efficacious. Thus we read:

“Aside from buying associations maintained by farmers, hardly any exist in this country. It is apparent, therefore, that the consumer has much to do to work out his own salvation with regard to the prices that he pays. Potatoes were selling last spring in some places where there had been overproduction for twenty cents and in some places for even nine cents per bushel at the farm, while at the same time city consumers in the East were paying fifty to seventy-five cents per bushel, although there was nothing to prevent them from combining to buy a carload or more of potatoes directly from the grower and for delivery directly to themselves.”

As similar abnormal differences between the price at the farm and the price to the consumer are found in varying degrees through the whole list of agricultural products, no argument is needed to make clear the economic value of the buying association, from the consumer’s point of view. And the logical outgrowth of such buying associations, especially in the larger centers, is the cooperative store. When such cooperative movements gather sufficient headway one factor in the cost of living, the middleman and his profits, will be practically eliminated. The same cause would be furthered to some extent by an adequate parcels post, which, by cutting express charges, would also help to smooth the way between producer and consumer.

*James Wilson was appointed Secretary of Agriculture by President William McKinley in 1897 and served until 1913. (Source: Wikipedia)

More reading on food co-ops and cooperatives as business models

Co-ops as Businesses

Cooperatives – the business model of the future

Rick Adamski, Full Circle Farm, on Co-operatives and Partnerships

Food Co-ops Grow Up – No Longer All Crunchy Granola and Birkenstocks

Food Co-ops

By Land or By Sea: Port Townsend Food Co-op

PCC Natural Markets – Co-ops in the 21st Century

Natural Food Co-ops: Putting Local Sourcing Into Practice

Food Front Co-op: Different Is Good

Central Co-op – Strongly Committed to Democracy, Community, and Sustainability

The Moscow Food Co-op – Small, Determined, Successful

Skagit Valley Food Co-op: Not Too Small, Not Too Big, Just Right