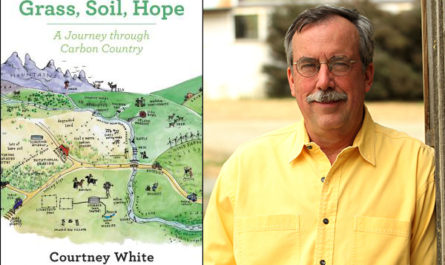

The author of this book, Grass, Soil, Hope, is perhaps best known as one of the founders of the Quivira Coalition. Quivira itself is the name of a legendary city of fabulous wealth sought by Francisco de Coronado, an early Spanish explorer of the American West.

The author of this book, Grass, Soil, Hope, is perhaps best known as one of the founders of the Quivira Coalition. Quivira itself is the name of a legendary city of fabulous wealth sought by Francisco de Coronado, an early Spanish explorer of the American West.

Courtney White came to the Quivira Coalition, an association of southwest ranchers, as an environmentalist. Originally with the Sierra Club, Courtney had petitioned against cows with the other active Sierrans but came to recognize conservation-minded ranchers who shared a love for the land as he did.

Gradually, a common ethic began to form with members of both groups who sought to restore the original grasslands of Arizona and New Mexico as a sustainable working landscape or ecosystem. The operative word was compromise and the modus operandi was stewardship.

The middle ground defined by collaboration and stewardship set the course of White’s activism from the organization of Quivira restoration work forward. It is important to understand that stewardship as reiterated in Grass, Soil, Hope and an earlier text, Revolution on the Range, the Rise of a New Ranch in the American West, is not a list of practices such as prescribed burning, damming of watercourses, rotational grazing, or “clumping” of cattle.

Grass, Soil, Hope, Courtney White (Chelsea Green, 2014).

Get your copy here; Bookshop will connect you with a bookseller online or on the street.

Rather, following in the footsteps of its originator Aldo Leopold, land stewardship is the broader expression of a conviction about the unit of management being an ecosystem and its treatment as right or wrong according to what maintains it in its natural state. Aldo Leopold was a forest and game manager for the U.S. Forest Service in the Southwest and later a professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin.

An important part of restoring an ecosystem according to Leopold is restoring its functions. This is where carbon enters the picture of grasslands as working landscapes in the Southwest, but also in all vegetated landscapes addressed in White’s book. In respect to climate, the sequestering of carbon by plants is a primary grassland ecosystem function, building soil fertility and helping retain moisture.

Grass, Soil, Hope is a compendium of sites and associated behaviors all pointing to some aspect of stewardship. The scope is worldly including farmers and ranchers in Australia but also very domestic describing the trials and tribulations of a rooftop vegetable grower in New York City.

Collaboration as opposed to division is expressed throughout. What is the plan? Really, whatever is discovered by the “carbon pioneer.” The goals vary but “carbon sequestration, building soil, storing water, growing nutritious food, building resilience, and including, restoring creeks to form –– it’s all one job.”

With the grass, the soil, and the resulting hope, how does scale determine value? Well, when shrinking the carbon footprint, according to Courtney White, every little bit counts. “Toss in the concept of sweet spots (as a restored delta wetland on Twitchell Island in California) as where big things happen in small places for a minimum amount of effort and cost. Wetland restoration provides a big bang for the buck for sequestering carbon.”

Courtney White’s book covers a lot of territory, both upon the landscape but also from a policy perspective. We can say Courtney was born into conflict with the “New Ranch” movement. And he uncovers conflict at every intersection along his own road to discovery. But perhaps what makes Grass, Soil, and Hope such enlightened reading is his optimism. All the individuals he encounters in his travels are at some stage of problem-solving and all the problems together fit a critical wholeness of concern no less than the heating up of the planet, the loss of biodiversity, the poisoning of soils and water and air, and the destruction of human health.

The means for achieving optimism in the face of adversity is community. But not one of groups sitting around tables but rather through seeking out the common ground and engaging in projects. The conclusion of the book focuses on proponents of the “new agrarianism” like Wendel Berry and Eric Freyfogle.

Both see agrarianism as the countervailing force to industrialism with its sins like “water pollution, soil loss, resource consumption, and the radical disruption of plant and wildlife populations.” Eric Freyfogle expands this range to include social conditions like a declining sense of community. Courtney White includes in the new agrarians “the carbon farmer or rancher who explores and shares strategies that sequester carbon in soils and plants, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and produce co-benefits that build ecological and economic resilience in local landscapes.”

Also by Courtney White

The Sun, by Courtney White (Early Hour Press, 2018)

Along the way, looking for human enterprise and land use that works to achieve a balance with Nature, Courtney White found time to write a mystery.

The Sun is a paperback right off the bookstand in the airport or train terminal of your choice. But it is also an allegorical stage set presenting a unique cast of characters, each experiencing anguish over what to do with a particularly well-situated piece of New Mexican land; to either foster its renewal and make a human reunion with it lasting, or something else.

In the story, “a young doctor inherits a large, beautiful property and must decide: What it is the ranch for? Oil-and-gas? Houses? Cattle? Fish? Wolves? A casino? A spiritual retreat? Complicating things, there’s a dead body and a mystery to solve.”

The ranch itself sits in the past with its intrinsic human history; the new human activity around it defies imagination and perhaps exceeds the capacity of functions the original ranch landscape was meant to serve. The causalities build with the desire to profit. And of course, each interest has their own idea of what that land use might be.

The setting, the characters, the contest all makes for a good story improved by the relevance of the natural landscape’s limits and the anguish of the ranches’ ecological defenders abides.

Get your copy here.