Around the world, women have traditionally managed much of food production and preparation while receiving little recognition, financial support, and education. Control of livestock production varies by culture and context; however, in general, men are responsible for large animals such as cattle, horses, and camels, while women manage smaller animals such as goats, sheep, pigs, and poultry (UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), The State of Food and Agriculture, 2010-2011). In Nicaragua, for example, women own around 10 percent of work animals and cattle but 55–65 percent of pigs and poultry.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (2009) also documents a phenomenon called the “feminization of agriculture” or the growing dominance of women in agricultural production, reflecting both an increase in the number of women and decrease in the number of men in the sector.

In the US, where most livestock production has been industrialized, including beef, pork, and poultry production, there is a distinct gender bias toward women in the farming of small livestock such as sheep and goats.

The most recent Census of Agriculture (2007) reported more than 300,000 women operating farms, up almost 30% from five years earlier. And women are more than twice as likely as men to operate farms with sheep, goats, and “other livestock.”

In 2007, there were more than 83,000 farms raising sheep, 90% of which were in flocks of fewer than 100 and 2/3 in flocks of fewer than 25. The same year there were about 27,000 farms raising dairy goats in herds averaging just 12. These farms are truly small businesses!

Many women in farming have had to develop their own production techniques, their own farming methods, and even their own animal breeds and bloodlines. And in the US, we’ve seen women become experts, teaching other young women to farm, and leading the food movement in small livestock production equal to or even beyond the contribution of academics with little or no field experience.

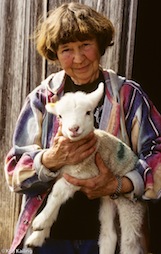

We highlight four women farmers raising small livestock (one of whom has retired after 44 years of sheep farming) to recognize the commitments they have made to what is essentially “women’s work” – that is, small ruminant husbandry. Farming is hard work and these women are all champions who have spent decades learning their craft and trade.

- Carey Hunter, Pine Stump Farms, Omak WA, has a herd of 45 doe goats and she makes fresh and aged farmstead cheese and yogurt. Carey projects 80 to 85 kids this year.

- Sue Brown, Amaltheia Dairy, Belgrade MT, and her husband Mel, will deliver between 400 and 450 kids from 260 doe goats. Sue makes fresh and aged farmstead cheeses from her goats’ milk.

- Clare Paris, Larkhaven Farm, Tonasket WA, raises dairy sheep, managing a flock of 58 ewes from which she makes aged farmstead cheeses. Clare’s flock will produce 100 to 120 lambs in 2014.

- Lea McEvilly, Caledonia MN, now retired after farming for 44 years, managed flocks of 300 to 360 meat sheep and in a season delivered as many as 300 to 325 lambs from about 160 ewes.

These women battle cold and exhaustion, relish the exhilaration of a successful lambing or kidding season and, devoted to their animals, are committed to going through it again year after year.

Cold Weather Lambing and Kidding

Whether sheep and goats are raised for meat or milk, they most often give birth in late winter or early spring. When the weather is so miserable in northern latitudes, why subject your animals – and yourself as a farmer – to bitter cold conditions for the delivery of baby lambs and goats? It’s all in the timing…

Timing of breeding and birthing is a matter of season, day length, and – first and foremost – economics. Breeding sheep and goats to give birth earlier in the calendar year means that lactation starts earlier for milking animals and cheese-making can begin earlier, and the young have longer to mature for meat animals.

Temperature and day length both affect the time when sheep and goats go into “heat” and are sexually receptive; the most natural time for sheep and goats to breed is August through December. In late summer and autumn, as days get shorter and temperatures begin to drop, the females enter the estrus cycle and breeding can begin. Until the ewes and does are impregnated they will continue to cycle every two to four weeks.

By keeping males separate from the females, it is possible to schedule birthing, which takes place approximately five months after conception. In snowy climates, like north central Washington, south central Montana, and southeast Minnesota, it is helpful to time new births with access to rapidly growing spring pasture for good milk production.

Cows, sheep, and goats, like all mammals, begin to give milk immediately upon the birth of their young and lactate until the babies are able to nourish themselves. Goats will give milk for approximately 10 months after kidding and sheep cease milk production by the end of September or early October as days shorten.

Shepherds and Goatherds – No Little Bo-Peep Here

Delivering dozens – or even hundreds – of lambs and kids, sometimes in weather as cold as -40°, is a monumental task. And from mid-January until mid-April, Sue Brown, Carey Hunter, Clare Paris, and, until she retired, Lea McEvilly, valiantly rise to the challenges and failures of the season and will, over their lifetimes, assist in the delivery of thousands of healthy animal and provide top-quality meat and cheese for an uncounted number of consumers.

In late January, Sue Brown starts delivering kids and in 2014 year she faced unusually cold temperatures, as low as -40° for the first waves of births. Good news for Sue is that her goats don’t seem to kid at night. “By 6 or 7 PM we just shut everything down,” says Sue. “They seem to have their babies starting early in the morning, at 6 AM or so.” Kidding on the farm goes on until May so the goats can provide milk for cheese production all year round.

This year at Amaltheia it took three people to deal with the low temperatures; watching the goats, helping when necessary, and drying the kids to keep them from freezing. Heat lamps and blow driers helped keep the goats warm. “It was so cold the blow dryers weren’t even blowing hot air. We burned the motor out on one and cycled through dozens of towels,” said Sue. Working as a team, the Browns had a survival rate of more than 90%, an excellent result considering that multiple births – which are common – can leave wet babies lying unprotected on the hay.

At Pine Stump Farms, Carey Hunter begins kidding at the end of February, with most of the baby goats born in February and March. Her birthing cycle runs through May when a smaller group of doelings – yearling does – will deliver. The longer cycle means that Carey can milk all year round.

To deal with the cold, Carey has “nurseries” that have 14 separate box stalls. “We let the moms room with the babies, and the nannies can hear each other but not see each other,” says Carey. “They are social animals and separating them makes it easier to work with the moms and babies. It also keeps new moms from getting distracted so they can concentrate on their babies.” If the kids need to be dried, she uses lots of towels to rub them and brings them into the living room to warm.

Lea McEvilly, on the other hand, rarely lambed before mid-March and finished in April. Even though she was past the worst of southeast Minnesota’s coldest temperatures, it was always cold – generally around zero at night. During a birthing cycle compressed into about 3 weeks, not counting a few stragglers, Lea almost always worked alone. Occasionally a friend and fellow shepherd, someone who knew what she was doing, would help.

“The hardest part,” says Lea, “was when I had a really tough delivery. Sometimes I’d have two or three in a row, and I couldn’t save all the babies. Maybe, just two out of three. It is hard to take, to lose one after five months’ gestation.”

There was only one year that Lea lost more than 4% of her lambs during birthing. That was the year that she had a 2-year old child, was recovering from a broken leg, and was lambing on crutches. Lea had 5 years over her career that she had no losses at all.

This year Clare Paris’ plan is to begin lambing the third week of March for approximately three weeks. By the end of March the weather is not severely cold, though she has occasionally lost a lamb from freezing. “One year we had a surprise drop to zero when I had both sheep and goats,” says Clare. “We had one kid who lost about an inch and a half of each of his ears from frostbite. We called him Frosty.”

Last year lambing went on for 6 weeks at Larkhaven; for Clare, that’s too long because late lambs won’t gain enough weight for slaughter by fall and no one wants to buy them for “finishing.”

There Are Rewards

Farming is hard work and livestock farming is especially hard in the winter, but there are rewards among the challenges. For Sue it’s when she’s able to help the occasional weak and sickly kid back to health. “I get a real sense of satisfaction when we’ve got one that isn’t doing well and we bring it back to health. I hate losing them!”

Sue also enjoys the recognition that she gets from customers and peers, “People love our cheese!” Amaltheia Organic Dairy now produces 17 different cheese products, three of which have been recognized by the American Cheese Society.

Clare finds the birthing process exhilarating. “It’s absolutely my favorite part of the whole process; I love rising to whatever is going on,” she says. “I like the lambing process – the imperative of the immediacy. I like dealing with the problems, figuring out what needs to be done. I like the feeling of competence that comes from long-term experience. I like being familiar with my flock, the record keeping. Keeping track of how their birthings go, comparing to the year before – the big picture part of it. I like the earthiness of it – how it all follows and is connected; the way it all works together.”

She also gets a great deal of satisfaction from the feeling of confidence that comes with long-term experience, “At one point I noticed that people were calling me more than I was calling someone else; it came on gradually. I enjoy it!”

The farming life is Carey’s reward, “I love the lifestyle, and I’m an animal person. I like going out and talking to the animals, seeing how they’re doing. Making sure the animals are comfortable – that they have what they need. We’ve built a lot of infrastructure for them – barns, corrals, pens, and shelters. When they’re happy, I’m happy.”

It was not all roses for Lea; she says, “There were terrible times that I got through somehow. I picked up the pieces and kept going; it felt hopeless at times.”

Retired after years of farming and decades of lambing seasons, she found her biggest rewards in the land, “I’m a born conservationist, and I worked hard to improve the pastures. Seeing the land, the crops, and the woods thriving and so lush, I loved just being on the land. I really miss it.”

Over more than four decades Lea was instrumental in strengthening the sheep industry in Minnesota through her leadership and participation in the South East Minnesota Sheep Producers Association (SEMSPA). She was the first woman to win the “Silver Bell Award,” presented by the University of Minnesota and the Minnesota Lamb and Wool Producers. Lea also organized a TeleAuction where SEMSPA members could sell their lambs to buyers all over the US, for as much as $5 per hundredweight over local meatpackers.

And now more than 50 years after Lea’s first experience lambing, her own “Hi-5” bloodline, a 5-way cross that produced prolific, healthy, and nurturing ewes, is still popular. Even now Lea occasionally gets calls looking for breeding stock.

Women in Agriculture

Each of these four women – Sue Brown, Carey Hunter, Clare Paris, and Lea McEvilly – is closely linked to the land, her family, and her animals. They have developed their own production techniques, their own farming methods, and even their own animal breeds and bloodlines.

And all four are connected by gender, vocation, and avocation to women farmers around the world and reflect the rapidly changing roles and status of women in agriculture. “Women hold up half the sky” and closing the gender gap in agriculture in developing and under-developed countries will generate significant gains for both the agriculture sector and for society as a whole.

Women are the majority of the world’s agricultural producers, playing important roles in fisheries and forestry as well as in farming. Worldwide, women produce more than 50 percent of the food that is grown (FAO, 1995a).

Moreover, in many parts of the world, women are responsible for providing the food for their families, if not by producing it then by earning the income for its purchase. Finally, women are nearly universally responsible for food preparation for their families.

All this they do in the face of constraints and attitudes that conspire to undervalue their work and responsibilities, reduce their productivity, place upon them a disproportionate work burden, discriminate against them, and hinder their participation in decision-making and policy-making.

UN Food and Agriculture Organization (1996)

It is time we recognize the millions of women who produce, process, and prepare the food for the world. They are true heroes and without them millions more would go hungry.

* Chairman Mao Zedong, the leader of the People’s Republic of China from 1945 to 1976, famously said that, “In China, women hold up half the sky.” It is thought that he really wanted to double the country’s work force by including women as well as men; the phrase has since taken on significance describing women’s equality.

Additional Reading