Copyright by and reproduced with permission from Devon Peña, Professor of Anthropology,

University of Washington, Seattle WA.

Moderator’s Note: It is my privilege this time of the year to present the work of my undergraduate students at the University of Washington. This year I am presenting a series of outstanding blogs by students enrolled in my course on Environmental Anthropology. The large lecture format course introduces students to the field of environmental anthropology, which includes the study of Ethnoecology – the knowledge of ecology developed by indigenous and other traditional place-based peoples. The course also examines contributions from the fields of critical political ecology, which focuses on the role of science in the politics of environmental law, policy, and social movements.

Finally, we study aspects of environmental history, which focuses on the role of human societies – both small- and large-scale – in processes of ecological change and includes analysis of the history of ideas about the quality of the human-environment relationship. Like the class, these blogs seek to bridge all these approaches and more by providing entries that address local place-based knowledge and situate Ethnoecology within the context of politics and history.

The thirteenth entry in this series is about the Pacific Crabapple, an important native but unjustly maligned fruit tree. This is a very insightful report that discusses the environmental and cultural history including the traditional ecological knowledge associated with First Peoples relationship to the tree. The students turn to the contemporary context and address a wide range of issues involved in the use and conservation of the tree, which many people view with less than appreciative impressions. They also provide a detailed description of the agroecology of the tree.

The students discuss the decline of traditional uses and emphasize how this has been a result of the enclosure of tribal homelands and subsequent displacement of Native Peoples from their relations with ancestral lands.

________________________________________

Pacific Crabapple Tree

SWEET FOR THOSE WHO ARE PATIENT

Clay Patton | Alyssum Quaglia | Jordan Futran | Jonah Ury

[Jordan]

It was raining. I was cold and hungry. I was told it would be here, in the Crabapple Meadow. Instead, that open meadow, filled with picnic benches and probably a perfect spot for a summer picnic just a few months earlier, was lined with the more attractive Asian crabapple varieties and other more appealing hybrids of the Malus genus.

“Pacific crabapple, yeah, I think we have one of those,” said the man at the Graham Visitors Center, Washington Park Arboretum, “but I don’t know exactly where.”

So I looked and I looked. And I looked some more. It was wet and I was cold. But I found it. It wasn’t very big compared to the trees around it; it lacked colorful or fragrant blooms. It was really just a scraggly tree with turning leaves and small red pomes. To be honest, I’m not even sure if that was it; I wasn’t brave enough to slog through and get close to see clearly and if you ask me to take you there I probably wouldn’t even be able to find my way back; but I saw it. It was there. And like with this project it was worth looking hard to find and understand something that so often goes overlooked.

Malus fusca, Latin for brown apple is in my opinion a rather uninspired name. This fruit tree is commonly known as the Pacific Crabapple and was the Northwest plant we chose to focus our research on for this blog project. The etymology for the name of the crab apple is disputed, however I prefer the position that it is derived from the usage of the word crab as sour and acerbic in temperament, matching the fruit this plant produces.

Ciciḥʕaqƛ (click on the little arrow to listen) is the Ehattesaht Nuchatlaht word for crabapple (Mary Charlie 1991). The Quileute word for the Pacific crabapple can be literally translated as “hurts the tongue” (Gunther 1973:38), again referring to the fact that the fruit of this tree often bears sour and bitter fruit.

The crabapple is a member of the Rosaceae family, a group of flowering plants that includes 2,800 species (Stevens 2012). It is interesting to note that this family includes the roses (as the name implies) as well as many common edible fruits like cherries, strawberries, peaches, and others. The genus of our plant is Malus. This genus includes all wild and domesticated cultivars of apple trees. Although this specific variety of crabapple is not related to modern domestic cultivars grown in this region as well as well as any of the other North American crabapple taxa, it can trace its lineage back to Asian wild apples. This genetic similarity indicates the likelihood that the plant may have been brought along with humans on the great migrations across the Bering Strait that presumably filled the Americas with people for the first time (Routson et al. 2012:330). Native people contest that idea and claim they are of this place – autochthonous.

Upon arrival, this species proliferated along the entire West Coast of the United States, stretching through Canada and even into southern Alaska (Kartesz 2012). A small tree reaching a maximum of about 12 meters, the Pacific crabapple blooms with beautiful white and pink blossoms in late spring. The fruit to which the tree bears name are small yellow to red pomes found in clusters.

[Clay]

At first glance, the crabapple tree may appear to be a little underwhelming. Its diminutive sour fruit is generally disfavored by people who are used to eating the super sweet commercial apples found in grocery stores, its wiry branches make it a poor climbing tree, and its short stature fails to produce the sense of awe one gets from craning their neck upward at a Redwood or a Douglas fir.

Nevertheless, the crabapple tree holds a special place in my memories. Memories of mowing my next-door neighbor’s lawn in the early fall amidst the sound of fallen crabapples exploding like firecrackers as they hit the blades of the mower; Memories of tormenting my little sister by throwing rotten crabapples at her, stolen from the neighbor’s yard. Seeing the cherry trees blooming in the UW quad reminds me of the crabapple blooms back home – they were the first flowers of spring.

These memories give me a sense of place and create a connection between the town I grew up in and myself. My connection with the crabapple tree, however, pales in comparison to the relationship it shared (and continues to share) with the native people of the Pacific Northwest who depend on it for sustenance and medicine. For them, the crabapple long has held special importance.

[Jonah]

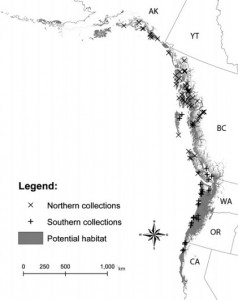

The Pacific Crabapple tree has been growing in Northwestern North America longer than any other species of ornamental fruit. Malus Fusca currentlyinhabits land as far north as southeastern Alaska and as far south as the coast of Northern California. The map below shows the extent of its range. The Pacific Crabapple tree grows in two lifezones, ranging from grasslands to foothills (sea level to mid elevations). The tree usually grows in moist environments; either in open wetlands or near bodies of water such as lakes, ocean, river mouths, etc. (Glover 2011)

Native groups from British Columbia all the way down through the bioregion of Cascadia (defined by the Columbia River watershed) used the Crabapple tree for various purposes. In Western Washington, some of the First Peoples to use this wild apple are the Cowlitz, Quinault, Samish, Makah, and Muckleshoot (Green River) (Gunther 1973:38). These tribes have accessed the crabapple tree in various ways depending on the particular region they inhabit.

[Clay]

The agroecology of the crabapple is therefore highly variable depending upon both the ecological conditions in which it grows as well as the culture that uses it. For example, the Samish of the San Juan Islands have not historically or actively cultivated crabapples. Instead in more traditional times, as they hopped from island to island they utilized crabapple trees as they went.

Their strategy of opportunistic [sic] foraging contrasts with those of more stationary tribes such as the Wakashan of British Columbia who long have tended small crabapple tree orchards. These orchards are not only for agriculture and also provide habitat for wildlife and understory plants that grow well under the shade. Specifically designated families have always cared for the Samish orchards and stewardship is still passed down along family lines, which maintain their traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) of the plant from generation to generation (Routson et al. 2012:326).

This TEK is not limited to the crabapple as a single and isolated species and instead extends to embrace an understanding of the tree’s interactions with other organisms. For example, the Muckleshoot say that wild crabapples provide food and habitat for pheasants and grouse and that sometime even bears enjoy the fruit (Gunther 1973:38). Many birds eat the fruit that remains on the trees in winter and the tangled lower branches of the tree provide protective cover for small mammals.

[Jonah]

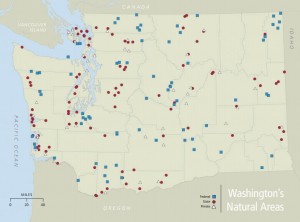

The Pacific Crabapple tree has largely fallen out of use among many First Peoples of the Pacific Northwest. This is partly because so many of them have suffered from the enclosure of their homelands and have been displaced onto reservations. The image below shows how each large regional group (at times multiple tribes) was unfairly displaced onto these small pieces of land. The Samish (originally from the San Juan Islands) are a good example of displacement as they were forced to move to the existing Swinomish Reservation (Wikipedia 2012).

Native peoples have clearly established ties to and place-based knowledge of the land in which they have lived for countless generations. The breaking of those ties via enclosure and violent displacement contributes to the dissolution of traditional use of the Pacific crabapple. Additionally, the advent of modern hybrid apple agriculture has diminished the commercial value of crabapples. This denies Native people a potential source of revenue.

[Clay]

One reason for the general lack of awareness of the crabapple in modern times is its taste: The crabapple is generally perceived as unpleasantly sour and acidic. Indeed, I remember being very disappointed by their sourness as a child. However, during my trip to the Washington State Arboretum I was able to taste several different varieties of crabapple, and each had a distinctive, pleasant taste. Almost all were very tart and had tough flesh, but one yellow variety called Malus “Sundog” was actually quite sweet without being sour. This was probably because it was the only tree with fruit that was fully ripe and falling off the tree.

[Alyssum]

Many First Peoples of the area, including the Swinomish, Samish and Quileute tribes prefer to eat the Pacific Crabapple raw. However, some prefer to soften the fruit by storing it in water inside cedar boxes or baskets (Gunther 1973: 38). I find it interesting that in this day and age we would be rushing to alleviate the crabapple’s initial bitterness with sweeteners and preservatives, while locals understand how such unnatural methods are unnecessary. After generations of use of the crabapple, the native people of the region learned that the acidity of the fruit is all it takes to preserves it and that it becomes softer and sweeter over time. Today, the crabapple is most commonly prepared as a sweet jelly, but traditionally the fruit was simply cooked and mashed (Clay-Poole 2012).

[Jonah]

Before settlers came to Western Washington, Pacific Crabapple trees flourished in adapting to the sometimes-poor conditions of the cold and moist climate of the Pacific Northwest. Natives protected and respecting the tree as a part of their community. Westerners fail at times to understand how Natives have a deeper connection to their homeland and how no land of equal (or in many cases lesser) size is the same in any way from their true home. Once removed from their traditional surroundings it makes sense that many tribes would decrease the consumption and cultivation of crops like the Pacific Crabapple tree.

[Alyssum]

The Pacific Crabapple tree certainly did mean much more to Native Peoples than a tasty treat. Its wood is strong but lightweight, which makes for excellent tools. The Quileute people, for example, use the wood to fashion mauls for driving tent stakes, but also for hunting implements such as the prongs on a seal spear or the bait lure of a sea bass hook (Gunther 1973:38).

Perhaps the most important ethnoecological aspects of the crabapple tree for native people are related to its diverse medicinal properties and uses. The bark is the most potent aspect of the tree, and is used to cure or treat a wide variety of ailments. Most often, it is peeled and soaked in water. The Makah tribe drinks this concoction for intestinal disorders such as dysentery or diarrhea, whil the Klallam and Quinault use the same mixture as eyewash. The Swinomish and Samish tribes prefer to boil the bark and water, which they use to wash cuts and as a drink for stomach disorders. The Quinault also drink the boiled remedy to cure “any soreness inside, for it all goes through the blood.” It is served as a tea in Quileute tribes to lessen lung troubles (Gunther 1973:38).

Unquestionably, Native Peoples came to possess such valuable knowledge through generations of experience. As a member of the rose family, the Pacific Crabapple tree has a delicious and nutritious fruit, but its bark, leaves, and seeds contain a harmful toxin – a cyanogenic glucoside[i] known as amygdalin. The fruit entices animals and humans to eat and spread its genetic material, while poison protects the seeds from being destroyed in the process. The toxin, however, is also what makes this plant so invaluable medicinally in small doses (Moerman 1989:52-61).

First Peoples came to discover its benevolent function mostly likely the result of intuition that was trained and honed by years of cumulative traditional knowledge. Researcher Daniel E. Moerman from the Department of Behavioral Sciences at the University of Michigan-Dearborn suggests that people learned to attribute the telltale bitterness of a toxin to possible medicinal use (Moerman 1989:52-61). While this method is perhaps not “scientifically viable” by today’s medical standards, it has been tested and proven by generations of survival, endurance and wellbeing.

[Jordan]

It is interesting that the Pacific crab apple – a plant which proved so useful to the indigenous people of the Northwest – has been given little heed in more contemporary times by those who have come to live within its habitat. In 1972, the Washington State legislature passed the Natural Area Preserves Act, officially designating areas across Washington for “conservation purposes” (Washington State Department of Natural Resources 2012). The intent of this act is to prevent, in various capacities, human incursion and alteration of designated areas. It is not clearly documented how many Pacific crabapple trees are protected by the designations made possible by this law. However, it is clear that areas in which they are suited to grow are within some of the protected zones as seen in how the map below compares to the tree’s natural range along the Washington Coast.

In 1984, with the help of Dr. Tom Green of the International Ornamental Crabapple Society, Washington State University at Mount Vernon established a test patch of altered varieties of crabapple trees (Maleike 1996). These altered varieties, none of which included or were related to the Pacific crabapple, were grown to develop cultivars better suited to the Pacific Northwest’s cool and moist climate. Almost all varieties labeled and trademarked by WSU are advertised as ornamental and are touted for their superior resistance to endemic diseases and climatic adaptability. This official codification of an entire branch of the Malus genus, as ornamental, with limited culinary appeal and no other benefit, serves to denigrate the natural place and usefulness the Pacific crabapple holds in the Pacific Northwest.

Currently, the Pacific crabapple is not considered in jeopardy as a species due to destruction of plants or habitat, so it is generally given little regard in any official function. Its official classification is that of a broadleaf (deciduous) tree within the “Type N” riparian buffer zone[ii] (Schuett-Hames, Roorbach, and Stewart 2006). These riparian zones are part of an emergency policy put in place in 2000 by the Washington Forest Practices Board, to combat destruction, and aid in the restoration of fish-bearing stream ecology (Ehringer and Estrella 2007).

Although type N buffer zones are used to conserve non fish-supporting streams it is understood that changes in these upstream watersheds can impact the streams that they flow into, which do support fish. These buffer zones are used to protect stream and watershed ecology from the consequences of timber harvesting, diminishing effects of changes to key metrics (shade cover, temperature, silt content etc.), which often are impacted by commercial logging practices (Ehringer and Estrella 2007).

The Pacific crabapple is an excellent stream bank and soil stabilizer, making it an important species to consider when dealing with stream conservation. However, there is no official measure to artificially strengthen this species’ presence in these buffer zones to stem the anthropogenic harm to these watersheds. Hopefully, the institutionalized powers-that-be will understand that native species kept the streams clear and the rivers full of fish, and that by returning the riparian ecosystem back to its unaltered state would go great lengths in reversing the harm that has been perpetrated.

[Clay]

In conclusion, the Pacific crabapple tree has a unique and dense history of association and interaction with humans. However, its importance as a food crop and source of medicine has declined dramatically. Although there is no danger of its extinction as a species, the true danger lies in the extinction of traditional ecological knowledge and cultural usage of this plant. It is truly a shame that this remarkable species is so often overlooked in favor of homogenized commercial apples. So the next time you spot a crabapple tree: stop, take a bite of its fruit, and allow its sour taste to connect you with the environment and history of the Pacific Northwest.

Bibliography

Mary Charlie, “Ehattesaht Nuchatlaht Words,” First Voices website, audio recording from 1991, accessed on November 18, 2012, http://www.firstvoices.com/en/EhattesahtNuchatlaht/word/183c43b13fe6c5cc/wild+crabapple.

Scott Clay-Poole, “Ethnobotany– Shrubs/Trees,” Washington State Department of Transportation website, last modified 2012, accessed November 18, 2012, http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/Environment/CulRes/ShrubsTrees.htm#malusF.

William Ehringer and Stephanie Estrella, “Quality Assurance Project Plan: Type N Experimental Buffer Treatment Study: Addressing Buffer Effectiveness on Riparian Inputs, Water Quality, and Exports to Fish-Bearing Waters in Basaltic Lithologie,” prepared for the Washington State Department of Ecology, 2007.

Jennifer Glover, “Pacific Crabapple,” Dendrology Survivor website, last modified October 20, 2011, accessed November 18, 2012, http://dendrologysurvivor.wikispaces.com/page/diff/Pacific+crab+apple/266864776.

Erna Gunther, Ethnobotany of Western Washington, University of Washington Press, 1973.

John T. Kartesz, “Plants Profile: Malus fusca (Raf.) C.K. Schneid. Oregon crab apple,” USDA NRCS National Plants Database website, last modified 2012, accessed on November 18, 2012, http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=MAFU

Raymond Maleike, Gary Moulton, and Jacqueline King, “Crabapple Varieties of the Pacific Northwest,” Washington State University website, 1996, accessed on November 10, 2012, http://gardening.wsu.edu/library/best001/best001.htm.

Daniel E. Moerman, “Poisoned Apples and Honeysuckles: The Medicinal Plants of Native America,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly, Vol. 3, No.1 (1989): 52-61.

Kanin J. Routson, Gayle M. Volk, Christopher M. Richards, Steven E. Smith, Gary Paul Nabhan, and Victoria Wyllie de Echeverria, “Genetic Variation and Distribution of Pacific Crabapple,” Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, Vol. 137, No. 5 (2012): 325-32.

“Reservation Sites Served,” Evergreen State College website, last modified 2012, accessed November 18, 2012, http://www.evergreen.edu/tribal/reservation.htm.

“Samish,” Wikipedia, last modified May 28, 2012, accessed November 18, 2012, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samish.

Dave Schuett-Hames, Ashley Roorbach and Robert Conrad, “Results of the Westside Type N Buffer Characteristics, Integrity, and Fuction Study: Final Report. Prepared for Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Cooperative Monitoring Evaluation and Research CMER 12-1201, 2012. Available on-line: http://www.dnr.wa.gov/Publications/fp_cmer_12_1201.pdf.

Dave Schuett-Hames, Ashley Roorbach, and Greg Stewart, “Implementation Plan: Summer 2006 Sampling Event Westside Type N Riparian Buffer Characteristics, Integrity And Function Study,” prepared for the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, 2006.

P. F. Stevens, “Angiosperm Phylogeny Website Version 9,” last modified 2012, accessed on November 18, 2012, http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/welcome.html.

Washington Natural Areas Program,” Washington State Department of Natural Resources website, last modified 2012, accessed on November 18, 2012, http://www.dnr.wa.gov/ResearchScience/Topics/NaturalAreas/Pages/amp_na.aspx.

________________________________________

[i] A cyogenic glucosaide is a class of compounds that stores hydrogen cyanide, which is a dangerous poison that is toxic to humans and other mammals in high enough doses. Well-known examples, besides the apple seed, are the pits of fruits like peaches and apricots.

[ii] The “West side Type N riparian buffer zone” is currently classified as non-fish-bearing streams that can be rehabilitated as fish habitat. See Schuett-Hames, Roorbach and Conrad 2012.

________________________________________

About Devon G. Peña

A lifelong activist in the environmental justice and resilient agriculture movements, Devon G. Peña is a Professor of American Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, and Environmental Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. He also works on the family’s historic acequia farm in San Acacio, Colorado.

A lifelong activist in the environmental justice and resilient agriculture movements, Devon G. Peña is a Professor of American Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, and Environmental Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. He also works on the family’s historic acequia farm in San Acacio, Colorado.

A pioneering interdisciplinary research scholar and widely-cited author, his most recent books include Mexican Americans and the Environment: Tierra y Vida (U. of Arizona Press, 2005) and The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States (senior editor, Oxford University Press, 2005).

Dr. Peña is the Founder and President of The Acequia Institute, the nation’s first Latina/o charitable foundation dedicated to supporting research and education for the environmental and food justice movements.

Read this article as it was originally published here.